Manufacturing everywhere, capabilities somewhere: why China's industrial breadth doesn't mean technological omnipotence

Understanding the gap between production capacity and supply chain competence

A question is dominating policy debates across Western capitals: has China’s manufacturing dominance made Europe and the UK economically irrelevant? Does the West have “nothing to offer“ in a world where China produces across every industrial category?

The answer matters enormously for how advanced economies navigate US-China competition. Get it wrong, and countries either surrender economic relationships worth hundreds of billions annually or pursue ineffective restrictions that harm their own economies whilst failing to achieve security objectives.

The debate deserves better than binary thinking. My research on supply chain competence provides an analytical framework for moving beyond “engage or restrict” toward systematic, evidence-based strategy. Because whilst China’s manufacturing breadth is genuinely unprecedented, breadth doesn’t equal frontier capability at all technology tiers.

The breadth is real – and unprecedented

China is the only country in history with production capacity across all 41 major UN industrial categories, 207 medium categories and 666 small categories. From cutting-edge semiconductors to basic textiles, from commercial aircraft to solar panels, China produces domestically across every major industrial classification.

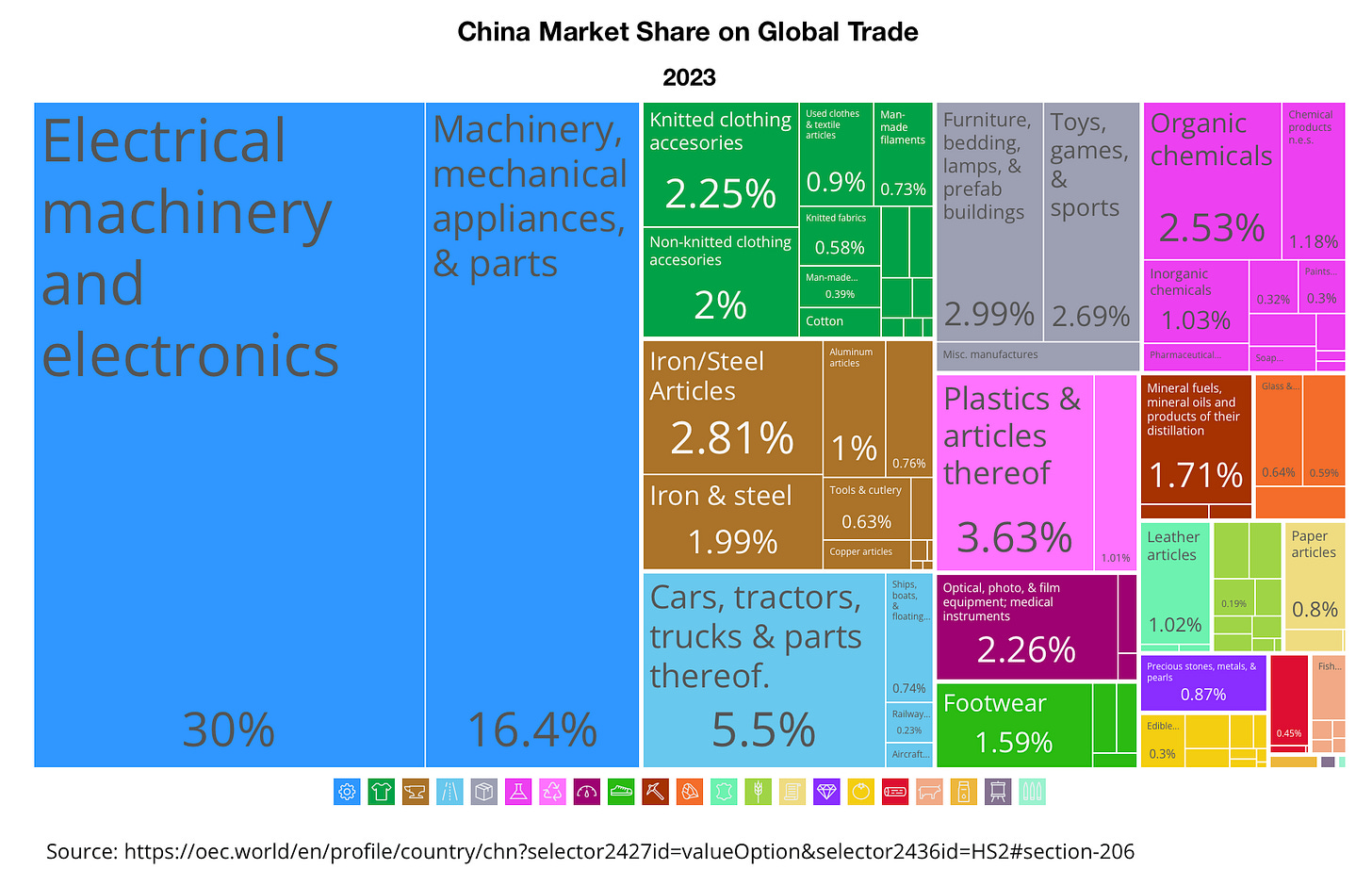

Producing one-third of global manufacturing output, $3.6 trillion in merchandise exports (2024), China is world’s largest producer in 220+ product categories. Figure 1 shows the breath.

But here’s where simple narratives break down under empirical scrutiny: production capacity doesn’t equal autonomous capability at all technology tiers. Export value isn’t the same with value-added. Many competitive product lines rely on the cost efficiency made possible through embedding in global value chains with parts moving in and out of a country. Plus, within every industrial category, quality tiers exist.

Figure 1: China’s export share in global trade by HS2 sectors, 2023

The supply chain competence framework

To understand persistent dependencies despite China’s breadth, I’ve developed a framework assessing whether China has mastered five critical elements:

Design capability: Can China design to frontier specifications?

Process knowledge: Can China manufacture at required quality and yield rates?

Testing and validation: Can China verify performance meets international standards?

Systems integration: Can China integrate components into complex systems?

After-sales support: Can China maintain and repair over product lifecycle?

Chinese production often demonstrates elements 1-2 but shows gaps in elements 3-5, creating persistent import dependence despite domestic production capacity.

Where dependencies persist and where they don’t

Where China has achieved complete supply chain competence:

Clean energy technology demonstrates this clearly. Solar panels (80% global capacity), EV batteries (77% global production) – quality now matches European specifications whilst maintaining 35-40% cost advantage. CATL and BYD battery technology equals or exceeds LG and Panasonic. China has all five supply chain competence elements here. Export controls on Chinese goods would be ineffective and merely increase energy transition costs.

Where strategic dependencies remain:

Cutting-edge semiconductors: China imported $415 billion in 2023, up 15% from 2022. Despite $150 billion annual investment, China remains 5-10 years behind on EUV lithography (ASML monopoly). Missing elements: testing equipment, lithography access, global service networks.

Aircraft engines: COMAC’s C919 (December 2022) uses CFM LEAP engines. China’s domestic alternative fails certification after 15 years. Engine development requires 20-30 year cycles; parity before 2035-2040 unlikely.

Precision equipment and control boards: China continues importing substantial volumes of German and Japanese precision machine tools and high precision control boards despite domestic production capacity. Chinese manufacturers pay premiums for German and Japanese equipment in applications requiring ultra-high precision.

Industrial software: China remains heavily dependent on Western engineering design software. CAD/CAE/EDA tools (Siemens, Dassault, Cadence, Synopsys) dominate Chinese manufacturing and chip design. China’s domestic software ecosystem lacks the accumulated user base and standards integration that create switching costs.

When weaponisation works, and when it doesn’t

Understanding supply chain competence reveals when weaponised interdependence can work versus when cooperative interdependence persists.

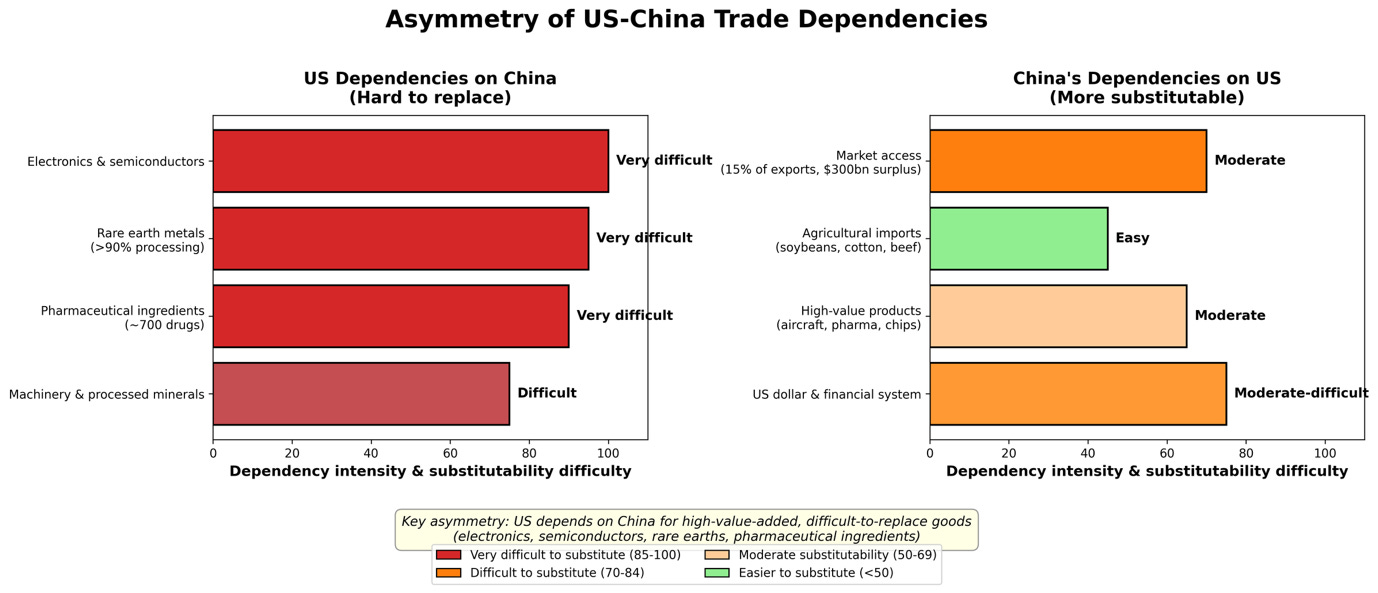

The critical insight: weaponisation only works under rare and specific conditions. Where these don’t hold – which is actually most of trade – cooperative interdependence not only persists but is economically rational for all parties. Figure 2 shows the leverages of the US and China with each other.

Figure 2: Asymmetry of US-China trade dependencies

Weaponisation requires three conditions to simultaneously align:

Asymmetric dependencies – one party significantly more dependent. US restricting semiconductor equipment works because China is 70% import-dependent and alternatives don’t exist.

Network centrality – control over infrastructure chokepoints. SWIFT payment systems, GPS, EUV lithography. These are genuine bottlenecks where alternatives don’t exist or take decades to build.

Low substitutability – the targeted good cannot easily be replaced. During 2018 trade war, US-China soybean trade collapsed from 48% to 6% market share within 18 months as Brazil substituted. Permanent shift. However, substitutability can emerge over time as China builds capability. Weaponisation is dynamic, not static.

These three conditions align in remarkably few sectors. Even within semiconductors – most frequently cited example – weaponisation effectiveness varies dramatically by technology tier.

Cooperation persists despite tensions

The data shows cooperation continuing across major economies:

Germany-China trade reached record $255 billion in 2023 despite “de-risking” rhetoric. Why? Mutual dependency. German manufacturing depends on Chinese supply chains; China needs German automotive technology and precision equipment. German FDI into China actually increased in advanced manufacturing sectors. Businesses are doubling down on interdependence, becoming more strategic about where.

Semiconductor supply chains demonstrate cooperation persisting even in the most “weaponised” sector. Taiwan produces chips, Japan supplies materials, Netherlands provides equipment, US designs architecture – no single country can weaponise without destroying the entire ecosystem and its own capabilities.

Services trade continues growing. China remains the largest market for international education – 700,000 Chinese students abroad represent approximately $30 billion annually. Financial services, legal services, management consulting all show sustained growth. The reason: services are far less susceptible to weaponisation than goods.

China remains the largest source of international students globally, with over 1 million Chinese students studying abroad as of 2023. Chinese tourists are equally significant – in 2023, Chinese travellers spent $196.5 billion on international travel, topping global rankings ahead of the US ($150 billion), Germany ($112 billion), and UK ($110 billion). Financial services, legal services, and management consulting all show sustained growth. More will be demanded in the coming years with the largest scale of business migration in the economic history. The reason: services are far less susceptible to weaponisation than goods. Restricting chip exports is feasible through customs controls; restricting knowledge flows or tourism without inflicting enormous self-harm is not.

Western dependencies on China are equally consequential. European automotive depends on Chinese batteries – CATL and BYD supply over 35% of European EV batteries with no alternatives at comparable scale or cost. American consumer electronics rely on Chinese manufacturing ecosystems (component suppliers, logistics, skilled labour) that cannot be rapidly replicated. Rare earth processing remains 85%+ concentrated in China – refining infrastructure and environmental management take decades to build. OECD clean energy transitions require Chinese solar panels and wind turbines at scales and prices domestic alternatives cannot match. The relationship is genuinely interdependent – attempts to weaponise from either direction impose significant costs, which is why cooperation persists despite geopolitical tensions.

Implications for trade policy

The supply chain competence framework reveals where dependencies are genuine and persistent versus where they’re already eroding or can be substituted. Understanding these distinctions matters for any country navigating US-China competition.

Where weaponisation conditions exist – asymmetric dependency, network centrality, low substitutability – controls can be effective. Where these conditions don’t hold, restrictions risk imposing costs without strategic benefit.

Room for cooperative interdependence exists. The evidence shows it requires honest assessment of where genuine strategic vulnerabilities exist (not everything is strategic), institutional mechanisms that create mutual vested interests (contracts, joint ventures, regulatory alignment), and distinguishing between security concerns and protectionist capture.

The challenge is moving from framework to implementation: which specific technologies warrant restrictions, where do controls exploit genuine dependencies versus impose costs without benefit, how do different countries’ economic structures create different trade-offs?

These are empirical questions requiring systematic, sector-by-sector analysis. Binary “engage or restrict” thinking doesn’t capture the reality of selective engagement based on security concerns, control effectiveness, and economic impact.

What’s next in this series

The supply chain competence framework reveals where dependencies exist and why they persist, but the really interesting questions come next. How do firms and governments actually respond when the ground shifts beneath them? Who adapts successfully, and who gets caught flat-footed?

Consider: Brazilian soybean farmers became global powerhouses in 18 months because of a US-China trade war. ARM Holdings licenses chip architecture to 95% of smartphones globally, including every Chinese mobile manufacturer, whilst staying headquartered in Cambridge. Pop Mart turned a Hong Kong artist’s Nordic folklore-inspired monster dolls into a $1 billion global brand. French luxury houses navigate China relationships entirely differently than German automakers. Each story reveals something about how economic power actually works in practice.

Future posts dig into these dynamics:

· China’s supply chain resilience: Soybeans rerouted in 18 months. Semiconductors taking years. EUV lithography might take decades. Why such different timelines?

· France’s strategic autonomy: Macron’s approach looks nothing like Germany’s industrial pragmatism. What can post-Brexit Britain learn from both?

· From Barbie to Labubu: When did China stop being “the world’s factory” and start creating global cultural phenomena? The shift matters more than most realise.

· Services trade dynamics: One million Chinese students abroad, $196.5 billion in annual tourist spending. Try weaponising that without shooting yourself in the foot.

· Strategic positioning frameworks: How countries can move beyond reactive crisis management toward systematic evaluation of where to align, where to diverge, where to double down.

The global economy is complicated. But understanding dependencies – where they exist, how they formed, what they mean for leverage – cuts through a lot of noise. And frankly, some of these stories are too good not to tell.

More to come.

Really strong framwork on supply chain competence. The five-element breakdown (design, process, testing, integration, after-sales) explains why China dominates clean energy but stil depends on aircraft engines and EUV lithography. The weaponization conditions are especially insightful, most people miss that asymmetric dependency alone isn't enough, you need network centrality and low substitutability too.